Asia

Are We In The Renaissance Of Arab Cinema?

Image: Shutterstock/JPRichard

Are We In The Renaissance Of Arab Cinema?

After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire at the conclusion of World War I, the Arab world was split between the imperial powers of Britain and France. This part of the world was bereft of its own cinematic culture until the individual nations slowly asserted their independence between the ‘20s and ‘60s. Suddenly, film was a part of the widespread Arab culture that dominates much of the Middle East and North Africa. And that meant something.

“Getting into industrial film production was considered a national achievement in the former Arab colonies and protectorates,” wrote film scholar Viola Shafik in her book Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. “The acquisition of cinematic techniques was a sign of progress and offered a real opportunity to expand economically. On the political level, cinema was … giving the formerly colonized a chance to challenge Western dominance, at least on the screen.”

Unfortunately, the social conservatism of most of these emerging Arab states led to censorship and nationalization, often hobbling the capabilities of Arab film industries. In recent years, however, Arab cinema has shown signs of resurgence on the global scale, though it still faces many challenges.

Jordan, for example, has thrived in recent years as a shooting location for filmmakers looking to recreate the exotic deserts of Saudi Arabia in a more hospitable locale, hosting shoots for films like Zero Dark Thirty. Even more remarkably, 2016 marks the first year a Jordanian film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

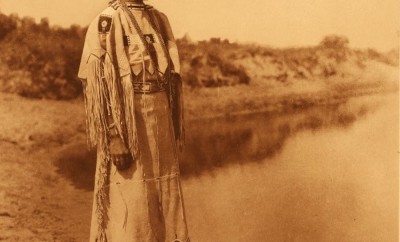

That film was Theeb, a uniquely Jordanian adventure story about a young Bedouin that guides a British soldier during the Arab revolts that was met with critical acclaim. The high-profile nomination sent a wave of excitement through the newly-resurged Jordanian film industry. Only nine years ago, Captain Abu Raed (2007) marked the nation’s first independent feature in fifty years.

The authentic film starring real Bedouins can be seen as another in a long line of recent cinematic triumphs to come out of the region, helped along by the advents of digital distribution and new production tools. The increased quality of filmmaking and the regional social movements crystallized in film have many scholars trumpeting a new golden age of Arab cinema, personified by the international acclaim of Theeb.

The new wave of challenging independent films coming from the Arab world stands in stark contrast to the previous few decades of Arab cinema. From the ‘40s to the ‘60s, Egypt was at the forefront of regional cinema for their successful melodrama and musical films, a production model neighboring nations often tried to emulate.

It was in the ‘60s that control of Arab cinema began to shift from the private sector to increasingly conservative governments, leading to a general decline in the quality and quantity of films produced. Censorship in all the area’s nations hurt the ability of native filmmakers to produce boundary-pushing or controversial films. From the ‘70s to the early 2000s, the Arab film industry languished without much freedom of expression to speak of.

Despite the promise of the Arab Spring movement, the national film industries remain mostly unchanged today. But that hasn’t stopped independent Arab filmmakers from creating powerful, unique films in recent years, even without much investment. The Yacoubian Building, a 2006 Egyptian film, portrayed an openly homosexual character, for example, while the politically-daring Moroccan film Starve Your Dog confronted the Interior Minister’s crackdown on freedom of speech in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

“If you look at Arab cinema in the ’80s, ’90, 2000s, we did not dare to put the people who have tormented us on trial in this way,” said film festival curator Rasha Salti.

Before, during and in the wake of the Arab Spring, the new so-called golden age of Arab cinema offers filmmakers and viewers alike the opportunity to confront and discuss the realities of Islamic and Arab cultures and their place in the modern world. As The Atlantic summarizes, “Arab cinema reflects this complex question of what it means to be Arab. It can feel like a pretty capricious ideological state, one that toggles between demands for cultural revolution and reinforcing conservative values.”

The film industries of the Middle East and North Africa still have big hurdles to overcome, including the lack of cinemas for distribution in the region, denying Arabs the chance to see local films that are praised on an international scale. Most TV stations are operated by the state and reject controversial or unusual films.

The success of Theeb and other films that examine Arab cultural heritage show steps being taken in the right direction, even if the movement is only onscreen so far.

In a progressive and exciting move, Theeb is getting an unprecedented theatrical re-release in the region.

0 comments